《纽约时报》2021年优秀美本申请文书出炉!!内含16-21年文书合集福利,必领!!

从2013年开始,美国最著名的媒体之一,《纽约时报》,都会邀请数百名当年的大学申请者分享他们的申请文书,并从中选出优秀的文书刊登在官网上。

《纽约时报》每年只会评选5篇左右思路和文笔俱佳的文书;而这些文书的含金量和重要性自然是不言而喻。

首先,在美国本科的申请当中,申请文书是一个至关重要的因素。在申请这个Holistic Review (整体评价)的过程中,文书无疑是最好的,甚至是唯一能够让学生直接展示自己性格,思想和价值观的材料。惠宜美本团队的多位前招生官也曾经表示,他们更加喜欢真情实感,有鲜明风格(搞笑,伤感或艺术等)的文书;也曾经有过因为出色的文书而将学生推荐给委员会作为录取后补的经历。另外,《纽约时报》每年文书评选都有不同的主题,包含生活的各个方面;并且学生背景也非常多样,对于目标不同背景不同的广大留学生群体极有参考价值。

我们在此为大家带来了两篇今年《纽约时报》刊登的优秀文书,并且就文书的亮点部分进行了点评,希望能给准留学生们带来帮助。

01

文书作者:Hoseong Nam

毕业学校:Hanoi, Vietnam — British Vietnamese International School

Despite the loud busking music, arcade lights and swarms of people, it was hard to be distracted from the corner street stall serving steaming cupfuls of tteokbokki — a medley of rice cake and fish cake covered in a concoction of hot sweet sauce. I gulped when I felt my friend tugging on the sleeve of my jacket, anticipating that he wanted to try it. After all, I promised to treat him out if he visited me in Korea over winter break.

尽管有喧闹的街头音乐、街灯和熙熙攘攘的人群,人们还是很难不被街角的小摊所吸引。小摊上卖着热气腾腾的炒年糕——一种米糕和鱼糕的结合体,上面涂着甜辣酱。我咽了一口口水,然后我感觉到我的朋友在拽我的夹克袖子,我以为他想尝试一下。毕竟,我答应过,如果他寒假去韩国看我,我就请他出去玩。

The cups of tteokbokki, garnished with sesame leaves and tempura, was a high-end variant of the street food, nothing like the kind from my childhood. Its price of 3,500 Korean won was also nothing like I recalled, either, simply charged more for being sold on a busy street. If I denied the purchase, I could console my friend and brother by purchasing more substantial meals elsewhere. Or we could spend on overpriced food now to indulge in the immediate gratification of a convenient but ephemeral snack.

炒年糕的杯中放着芝麻叶和天妇罗,这是一种高端街头小吃,跟我小时候吃的一点都不像。它的价格是3500韩元,跟我记得的也不一样,只是在繁华的街道上卖的价格更高。如果我不买我可以在其他地方买更丰盛的饭菜来安慰我的朋友和兄弟。或者,我们可以现在就把钱花在昂贵的食物上,以享受方便但短暂的零食带来的即时满足感。

At every seemingly inconsequential expenditure, I weigh the pros and cons of possible purchases as if I held my entire fate in my hands. To be generously hospitable, but recklessly drain the travel allowance we needed to stretch across two weeks? Or to be budgetarily shrewd, but possibly risk being classified as stingy? That is the question, and a calculus I so dearly detest.

每一笔看似无关紧要的支出,我都会权衡可能购买的东西的利弊,就好像我的命运掌握在自己手中一样。慷慨好客,却不顾一切地花掉我们两周的差旅费? 或者在预算上精打细算,但可能会被归类为吝啬? 这个问题让我深恶痛绝。

Unable to secure subsequent employment and saddled by alimony complications, there was no room in my dad’s household to be embarrassed by austerity or scraping for crumbs. Ever since I was taught to dilute shampoo with water, I’ve revised my formula to reduce irritation to the eye. Every visit to a fast-food chain included asking for a sheet of discount coupons — the parameters of all future menu choice — and a past receipt containing the code of a completed survey to redeem for a free cheeseburger. Exploiting combinations of multiple promotions to maximize savings at such establishments felt as thrilling as cracking war cryptography, critical for minimizing cash casualties.

在我父亲的家庭里,由于无法获得工作,又要承担赡养费的沉重负担,我爸爸没有为经济拮据或衣食无忧而感到尴尬的余地。自从有人教我用水稀释洗发水后,我就修改了自己的配方,以减少对眼睛的刺激。每次去一家快餐连锁店,他们都要一张折扣券——所有未来菜单选择的参数——和一张包含已完成调查代码的之前的收据,用它来换取一个免费的芝士汉堡。利用多种促销活动的组合来最大化这类机构的储蓄,感觉就像破解战争密码一样令人兴奋,而破解密码对于减少现金支出至关重要。

However, while disciplined restriction of expenses may be virtuous in private, at outings, even those amongst friends, spending less — when it comes to status — paradoxically costs more. In Asian family-style eating customs, a dish ordered is typically available to everyone, and the total bill, regardless of what you did or did not consume, is divided evenly. Too ashamed to ask for myself to be excluded from paying for dishes I did not order or partake in, I’ve opted out of invitations to meals altogether. I am wary even of meals where the inviting host has offered to treat everyone, fearful that if I only attended “free meals” I would be pinned as a parasite.

然而,虽然在私人场合严格限制开支可能是有益的,但在外出时,甚至在朋友之间,花得越少,成本更高。在亚洲家庭的饮食习惯中,通常每个人都可以点一道菜,而总账单,无论你吃了什么或没吃,都是平均分配的。因为不好意思要求自己不为我没点或没吃的菜付钱,所以我决定不接受邀请吃饭。我甚至对主人请客的情况都很警惕,担心如果我只蹭饭,我会被视为寄生虫。

Although I can now conduct t-tests to extract correlations between multiple variables, calculate marginal propensities to import and assess whether a developing country elsewhere in the world is at risk of becoming stuck in the middle-income trap, my day-to-day decisions still revolve around elementary arithmetic. I feel haunted, cursed by the compulsion to diligently subtract pennies from purchases hoping it will eventually pile up into a mere dollar, as if the slightest misjudgment in a single buy would tip my family’s balance sheet into irrecoverable poverty.

尽管我现在可以进行t检测来提取多个变量之间的相关性,计算边际进口倾向,并评估世界其他地方的发展中国家是否有陷入中等收入陷阱的风险,但我的日常决策仍然围绕着基本的算术。我总有种挥之不去的感觉,被一种努力从购买中减去一分钱的冲动所诅咒,希望它最终会堆积成一美元,好像一次购买中最轻微的误判就会让我的家庭陷入无法弥补的贫困之中。

Will I ever stop stressing over overspending?

我能停止为过度消费而感到压力吗?

I’m not sure I ever will.

我不确定我以后会不会。

But I do know this. As I handed over 7,000 won in exchange for two cups of tteokbokki to share amongst the three of us — my friend, my brother and myself — I am reminded that even if we are not swimming in splendor, we can still uphold our dignity through the generosity of sharing. Restricting one’s conscience only around ruminating which roads will lead to riches risks blindness toward rarer wealth: friends and family who do not measure one’s worth based on their net worth. Maybe one day, such rigorous monitoring of financial activity won’t be necessary, but even if not, this is still enough.

但我知道一点。当我交出7000韩元,以换取两杯炒年糕,我和我的朋友,我哥哥我们三个共享,我意识到了我们仍然可以通过共享的慷慨维护我们的尊严。把一个人的良心局限在思考哪些道路才能发财致富,可能会使他对更稀有的财富视而不见:朋友和家人不以净资产来衡量一个人的价值。也许有一天,这种对金融活动的严格监控对我来说将不再必要,但即使不是,朋友和家长也足够了。

惠宜点评:

这位学生先从一段“不起眼”的经历引入:在路边看到炒年糕的小吃,但是因为价格犹豫要不要购买。其实到这里来看,经济问题的主题并不是那么亮眼,但是作者通过对心理活动的描写,体现了家庭贫困的背景对自己性格的影响和由此产生的生活习惯,给读者带来一种personal的感受。

作者还列举了非常多个人成长经历,生动的描绘出了一个在困境中仍然保持着积极乐观生活态度的青年形象。但是他没有满足于展示自己的优秀品质;作者用一种非常聪明的方式插入了自己对于统计和计算机方面的浓厚兴趣以及实力。

在文章的最后,作者仍然用积极的基调升华了主题:比起金钱,尊严、亲情和友情更加重要。本篇文章以小见大,自然地融入了学术性和对生活的思考,不失为一篇真实简单但仍然亮眼的文书。

02

文书作者:Adrienne Coleman

毕业学校:Locust Valley, N.Y. — Friends Academy

“Pull down your mask, sweetheart, so I can see that pretty smile.”

"摘下你的面具,亲爱的,让我看到你美丽的笑容"

I returned a well-practiced smile with just my eyes, as the eight guys started their sixth bottle of Brunello di Montalcino. Their carefree banter bordered on heckling. Ignoring their comments, I stacked dishes heavy with half-eaten rib-eye steaks and truffle risotto. As I brought their plates to the dish pit, I warned my female co-workers about the increasingly drunken rowdiness at Table 44.

当那八个人开始喝他们的第六瓶布鲁奈洛迪蒙塔尔奇诺时,我用眼睛报以一个熟练的微笑。他们无忧无虑的戏谑,几乎是在起哄了。我不理会他们的评论,把吃了一半的肋眼牛排和松露意大利调味饭堆进盘子里。当我把她们的盘子端到盘子池时,我警告了我的女同事:44号桌喝多了,很吵闹。

This was not the first time I’d felt uncomfortable at work. When I initially presented my résumé to the restaurant manager, he scanned me up and down, barely glancing at the piece of paper. “Well, you’ve got no restaurant experience, but you know, you package well. When can you start?” I felt his eyes burn through me. That’s it? No pretense of a proper interview? “Great,” I said, thrilled at the prospect of earning good money. At the same time, reduced to the way I “package,” I felt degraded.

这不是我第一次在工作中感到不舒服。一开始我把我的简历提交给餐厅经理时,他上下打量了我一下,几乎没有看简历。“嗯,你没有餐馆的经验,但是你知道,你长得不错。你什么时候可以开始上班?” 我感到他的眼睛灼烧着我的身体。就这? 没有假装成正式的采访? “太好了,”我说,想到能挣到好多钱,我就激动不已。与此同时,沦落到我“包装”自己的方式,我觉得自己受到了贬低。

I thought back to my impassioned feminist speech that won the eighth-grade speech contest. I lingered on the moments that, as the leader of my high school’s F-Word Club, I had redefined feminism for my friends who initially rejected the word as radical. But in these instances, I realized how my notions of equality had been somewhat theoretical — a passion inspired by the words of Malala and R.B.G. — but not yet lived or compromised.

我回想起我在八年级演讲比赛中赢得的那篇充满激情的女权主义演讲。作为高中时f字俱乐部的领导,我为朋友们重新定义了女权主义,而这些朋友最初拒绝这个概念太激进了。但在这些情况下,我意识到我的平等观念多少有点理论化—只是一种受到马拉拉和R.B.G话语启发的激情—但还没有真正体验过,也没有被真正被挑战过。

The restaurant has become my real-world classroom, the pecking order transparent and immutable. All the managers, the decision makers, are men. They set the schedules, determine the tip pool, hire pretty young women to serve and hostess, and brazenly berate those below them. The V.I.P. customers are overwhelmingly men, the high rollers who drop thousands of dollars on drinks, and feel entitled to palm me, a 17-year-old, their phone numbers rolled inside a wad of cash.

餐厅已经成为我现实世界的教室,等级制度透明且不可改变。所有的经理和决策者都是男性。他们制定时间表,决定小费数额,雇佣年轻漂亮的女人来服务和招待,还厚颜无耻地斥责职位低于自己的人。贵宾客户绝大多数是男性,他们是挥金如金的人,在酒上花上数千美元,他们觉得有资格把电话号码卷在一沓现金里,然后塞到我这个17岁的孩子手里。

Angry customers, furious they had mistakenly received penne instead of pane, initially rattled me. I have since learned to assuage and soothe. I’ve developed the confidence to be firm with those who won’t wear a mask or are breathtakingly rude. I take pride in controlling my tables, working 13-hour shifts and earning my own money. At the same time, I’ve struggled to navigate the boundaries of what to accept and where to draw the line. When a staff member continued to inappropriately touch me, I had to summon the courage to address the issue with my male supervisor. Then, it took weeks for the harasser to get fired, only to return to his job a few days later.

愤怒的顾客们误拿了通心粉而不是玻璃,一开始让我很恼火。从那以后,我学会了安抚别人。我培养了对待那些不戴口罩或粗鲁得惊人的人的自信。我很自豪能控制自己的桌子,每天工作13个小时,自给自足。与此同时,我也在试图把握该接受什么,以及该在哪里划清界限。有一名员工一直以不恰当的方式触摸我,我不得不鼓起勇气向我的男上司提出这个问题。骚扰者几周后被解雇,但是他几天后又回到了工作岗位。

When I received my first paycheck, accompanied by a stack of cash tips, I questioned the compromises I was making. In this physical and mental space, I searched for my identity. It was simple to explore gender roles in a classroom or through complex characters in a Kate Chopin novel. My heroes, trailblazing women such as Simone de Beauvoir and Gloria Steinem, had paved the road for me. In my textbooks, their crusading is history. But the intense Saturday night crucible of the restaurant, with all the unwanted phone numbers, catcalls and wandering hands, jolted me into an unavoidable reckoning with feminism in a professional world.

当我拿到第一份薪水,还有一堆现金小费时,我对自己做出的妥协提出了质疑。在这个物质和精神的空间里,我试图寻找自己的身份。探索课堂上的性别角色,或者通过凯特·肖邦小说中的复杂人物,都很简单。我心目中的英雄们是开拓性的女性,就像波伏娃和斯泰纳姆,她们为我铺平了道路。在我的教科书里,她们的十字军东征已经成为历史。但周六晚上餐馆里的激烈考验,充斥着所有不需要的电话号码、嘘声和乱动的手,让我在职业世界里不可避免地想到了女权主义。

Often, I’ve felt shame; shame that I wasn’t as vocal as my heroes; shame that I feigned smiles and silently pocketed the cash handed to me. Yet, these experiences have been a catalyst for personal and intellectual growth. I am learning how to set boundaries and to use my professional skills as a means of empowerment.

我常常感到羞愧; 遗憾的是我不能像我的英雄们那样大声疾呼; 羞愧的是,我假装微笑,默默地把递给我的现金装进了口袋。然而,这些经历一直是个人和智力成长的催化剂。我正在学习如何设定界限,并利用我的专业技能作为给自己助力的手段。

Constantly re-evaluating my definition of feminism, I am inspired to dive deeply into gender studies and philosophy to better pursue social justice. I want to use politics as a forum for activism. Like my female icons, I want to stop the burden of sexism from falling on young women. In this way, I will smile fully — for myself.

不断重新审视自己对女权主义的定义,启发我深入地研究性别研究和哲学,更好地追求社会正义。我想把政治作为激进主义的论坛。就像我的女性偶像们一样,我想阻止年轻女性们遭受性别歧视。这样,我将充分地微笑-为我自己。

惠宜点评:

在这篇文书中,作者花了很大的篇幅讲述自己作为一名年轻女孩在高档餐馆的打工经历。在工作中,她遭遇了非常多的“被物化”的经历:从餐厅经理到男顾客和同事,都对她做了很多不合适的行为。作者感到非常矛盾:一方面她不得不为了收入而妥协,一方面她又在因为女性被歧视而感到气愤。

但是作者没有只讨论这些让人不舒服的经历;她不停地在进行自我思考、抗争和改变。通过在课堂内外的学习和活动,她成长为了一个女权主义者,同时能够掌握与男性和周边人的界限感。通篇文章有两条主线:与骚扰她的人(周边环境)的抗争,以及和自我身份的抗争。

对现实情况妥协,我是否还能成为一个真正的女权主义者?作者提出了这个发人深省的问题,借此引出了自己对于性别研究和平权的决心,以及在相关领域的学习经历。通过深刻的思考和出众的学习潜力,这位学生成功打动了大学招生官。

不知道这两篇优秀文书是否有给大家带来一些文书写作上的启示呢?

惠宜教育美本团队另外整理了

2016-2021年《纽约时报》的精选文书合集,

请扫描下方二维码添加惠宜美本Vivian老师,

备注“纽约时报文书”进行领取!

公司简介

惠宜教育(PrepEduConsultingLLC)成立于美国教育之都波士顿,是美国本土高端专业教育咨询机构。惠宜教育是美国独立教育顾问协会(IECA)高级资深会员,美国大学招生咨询委员会(NACAC)会员,美国招生管理协会(EMA)会员及EMA2019年度华盛顿年会铂金赞助机构。创立至今,惠宜教育已经帮助来自美国、加拿大、新加坡、香港、澳洲以及中国内地许多城市的学生们成功申请到了优质的美国初中、高中及大学,其中绝大多数是美国东北部顶尖热门的私立寄宿学校和非常著名的大学。作为一家“小而精“的独立留学咨询顾问机构,惠宜教育始终把学生和家长的利益放在首位,秉承“高端、专业、诚信、尽责”的服务理念,从真正提高孩子的全面素质入手,为其提供专业的学术背景提升和课外活动规划,其认真、细致、人性化留学咨询服务获得了家长们极高的口碑。

团队介绍

惠宜教育由留美化学博士波士顿Jing博士创办。波士顿Jing博士从事全职留学顾问多年,身为顶级私立寄宿美高学生的妈妈,Jing博士是美国私立精英教育的受惠者、实践者与传播者,亲自实地、多次走访了美国东西部150多所学校,与许多私立初中、高中都建立起了密切的信任关系。团队成员均毕业于哈佛大学、达特茅斯学院、埃姆赫斯特学院、纽约大学等名校,汇集了顶级美高迪尔菲尔德学院(DeerfieldAcademy)和西城中学(WesttownSchool)的前招生官,圣保罗中学(St.Paul’sSchool)的人文学科老师,在加拿大、美国出生长大同时精通中英文的华裔文书老师等教育界精英,为学生提供高端到位的留学咨询和规划服务。团队负责大学申请的美国顾问老师曾在哈佛大学招生办协助工作,并曾长期担任哈佛校友面试官,对美国藤校的招生喜好及录取标准十分熟悉。

提供服务

申请服务:美初、美高、美本、夏校

规划服务:美初申请规划、美高申请规划、美本申请规划

单项服务:面试辅导、文书写作、面试陪同、英文精读、创意写作

395TottenPondRoadSuite404

Waltham,MA02451,USA

http://www.prepedu.org

加州大学缩减国际生入学名额?最新政策情况全解读

高考分数出炉了!考后赴美留学应该怎么办?

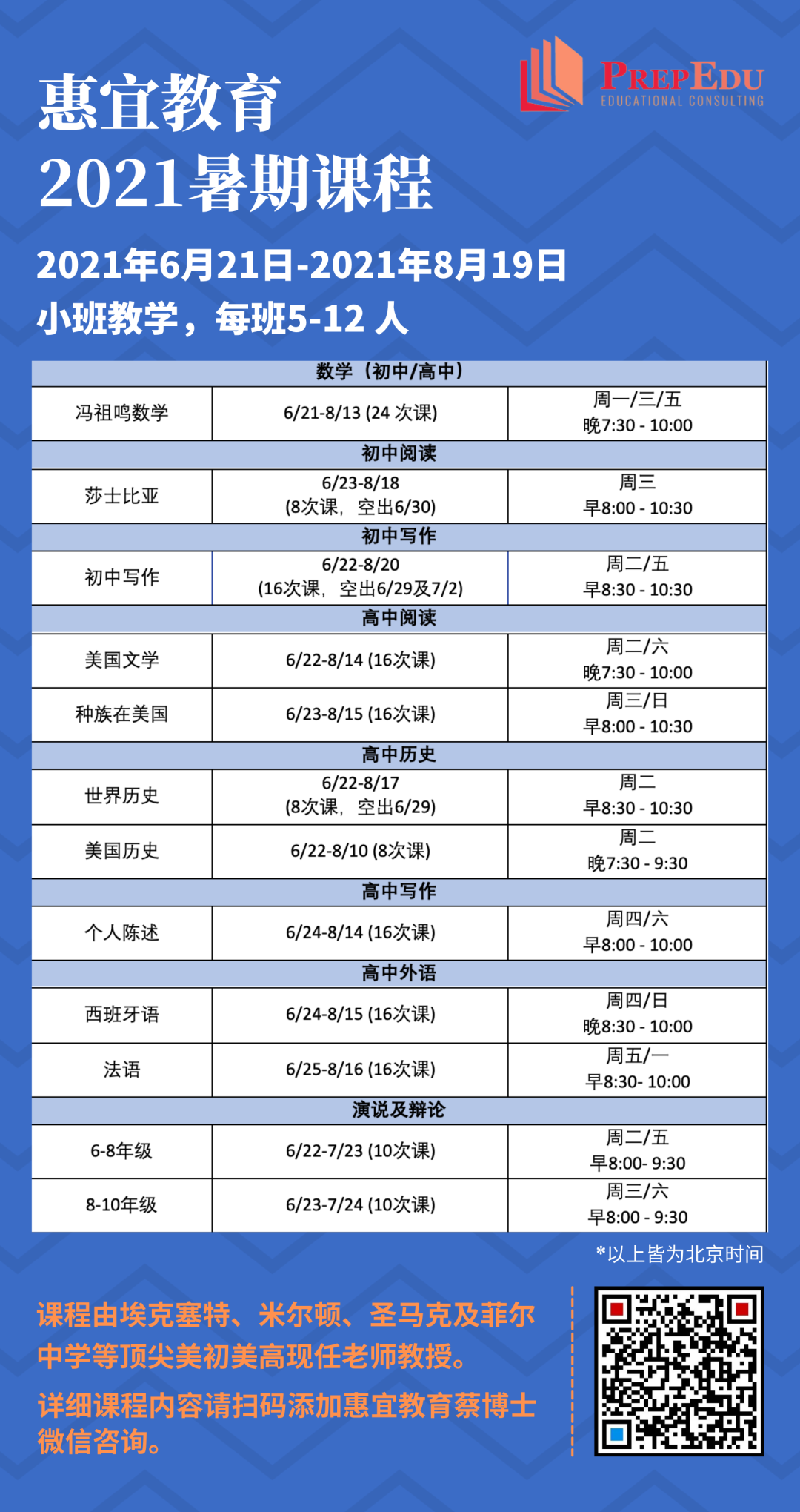

多位埃克塞特现任老师压阵!惠宜教育2021暑期课程隆重登场!

埃克塞特现任老师授课-惠宜教育2021暑期美高写作课程

米尔顿现任老师授课-惠宜教育2021暑期美国历史课程

埃克塞特现任老师授课-惠宜2021暑期西班牙语和法语课程

重磅!冯祖鸣老师推出美初美高数学衔接与强化课程!

惠宜教育2021暑期美国文学与人文历史课程

惠宜教育2021暑期美初英文阅读与写作课程

2021惠宜家长讲座第4场文字版: 上海男孩录取安多福

2021惠宜家长讲座第二场音频+文字版: 北京男孩录取Phillips Exeter

听故事 学经验 : 2020申请季惠宜家长心得分享讲座全集大放送!

2021惠宜美本录取捷报:13枚藤校,7成前35!

2021惠宜教育3.10 Offer雨 | 11枚前10!近八成前30!

2021惠宜家长讲座第一场音频+文字版: 大连男孩录取Choate Rosemary Hall

关键词

I’ve

文书

作者

美国

in the

最新评论

推荐文章

作者最新文章

你可能感兴趣的文章

Copyright Disclaimer: The copyright of contents (including texts, images, videos and audios) posted above belong to the User who shared or the third-party website which the User shared from. If you found your copyright have been infringed, please send a DMCA takedown notice to [email protected]. For more detail of the source, please click on the button "Read Original Post" below. For other communications, please send to [email protected].

版权声明:以上内容为用户推荐收藏至CareerEngine平台,其内容(含文字、图片、视频、音频等)及知识版权均属用户或用户转发自的第三方网站,如涉嫌侵权,请通知[email protected]进行信息删除。如需查看信息来源,请点击“查看原文”。如需洽谈其它事宜,请联系[email protected]。

版权声明:以上内容为用户推荐收藏至CareerEngine平台,其内容(含文字、图片、视频、音频等)及知识版权均属用户或用户转发自的第三方网站,如涉嫌侵权,请通知[email protected]进行信息删除。如需查看信息来源,请点击“查看原文”。如需洽谈其它事宜,请联系[email protected]。