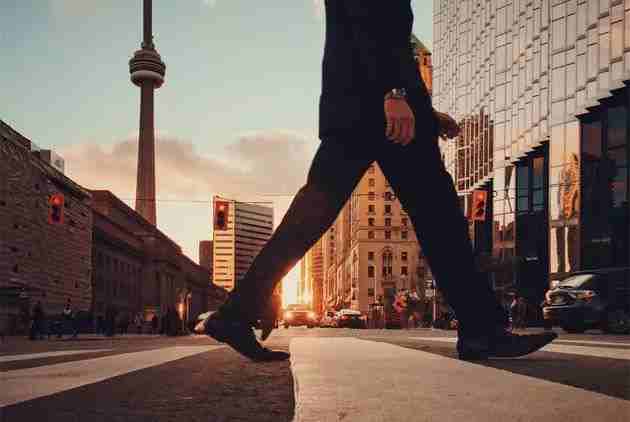

脸书高管:我曾像无数亚裔孩子一样渴望完美

在我小时候生活的大房子里,有一个美国梦。

我的父母对此深信不疑,所以他们买下了单程机票、带着几百美元的钞票和一口糟糕的英语、毅然决然地离开中国来到了这里。

实现美国梦要靠一个公式:好好学英语,考全班第一名,数学水平至少比同学领先一到两个年级,积极参加学术比赛(科学竞赛、数学竞赛等)并取得好名次,拿下SAT考试,作为毕业生代表在高中毕业典礼上上台讲话,上常春藤名校,读医学或法律专业,一辈子过上安安稳稳、舒舒服服的日子。

遗憾的是,这个公式对我的父母来说已经不管用了,他们来得太晚,第三轮才加入比赛的人是没有资格奢望赢得冠军的。他们在这里经历了无数个难捱的日子,白天去餐馆做服务员、晚上回到家夜夜失眠、他们一次又一次地向生活妥协,才最终挤进了中产阶级。

但我不一样。我还小,我的声带还没有开始发育,养成一口地道的英语是迟早的事;我的眼睛足够敏锐,感受和消化美国文化并不难。这一切于我而言是种希望,而我也像盖茨比一样,愿意穷极一生去追求这束遥远微弱、却富有力量的绿光。

我的记忆中有无数个遇到红灯停在路口的场景:衣衫褴褛的卖报人走过来,轻拍着我们的车窗,“要买报纸吗?要买报纸吗?”,每到这时,父母都会非常严肃地对我说,“Zhuo Li,看到了吗,如果你不努力学习、不考高分,将来就会像他这样到大街上卖报纸。”

这个公式很神奇,它在亚裔的圈子里似乎屡试不爽。每天都会有成功的消息传来:“文芳阿姨的女儿Sophia的SAT考了1590分,刚被哈佛录取。”“涛的儿子Frank进到了陶氏化学(Dow Chemical Lab)实习,还在科学展览会上拿了第一名。”“教会的Pam前一阵子登台演奏,得了钢琴表演州奖。”这些荣誉听起来是如此轻而易举,就像日程表上的安排一样被有条不紊地完成着。每一项成就的达成,都意味着这些孩子的履历上又将多一行文字,而说不定哪一行字最终就能换来一张梦寐以求的藤校入场券。年复一年,家里陈列奖杯的架子渐渐被摆满,除了妈妈每周末做家务时会打扫一下上面的灰尘以外,平时根本就不会有人多看一眼。

在我父母眼里,“完美”是一个非常明确的概念,实现“完美”的方法也总是固定的。

换句话说,100分就是完美,99分就是不完美。

我在高中时读过柏拉图的《对话录》。在书中,我了解到了“形式”这个概念。这个词非常吸引我。苏格拉底提到,我们身边的每一件事物,小狗、优雅、友谊……无论是有形的还是无形的,都有一种真正理想的形式。

然而,真正理想的形式是凡人无法看到的。我们像囚犯一样被困在洞穴里,眼前是光秃的灰色洞壁,身后是正在熊熊燃烧的大火。影子在洞壁上乱舞——小狗摇晃着尾巴,芭蕾舞者扭动着曼妙的身姿,三五好友随着歌曲节奏摇摆。

如果这是囚犯所看到的画面,他们会不会认为影子就是世界的本来面貌?洞壁上晃动着的影子真的能代表狗、优雅、友谊的本质和魅力吗?

但所幸,我们住在洞穴之外,与洞穴相距遥远。我们所看到的一切都是真实的、立体的,我们知道外面的世界是实实在在可以触碰得到的,远比影子的世界丰富多彩。

我太理解这个洞穴之喻了。它描述的就是我的生活:我一直在计算美国梦的公式给多少人带来了荣誉和掌声,却从未意识到,这个公式其实从来都是可望而不可及的。

美国梦值得吗?我一点一点地远离洞穴,每走一步,就离真实的世界又近了一点儿。

今天阳光真好,会议室里暖洋洋的,而此刻我的心脏却在砰砰直跳。又到了绩效评估季,经理马上就会把我的评估表带过来。

过去的这几年里,这样的场景每隔六个月就会上演一次。我坐在这把椅子上,重复着同样的复杂情绪:激动、恐惧、期待。这时的我是一个等待着圣诞礼物的孩子,满心欢喜地想着“他会不会带来一份非常出色的业绩表?等会儿我一定特别兴奋!我就说过你很棒吧?!”,却又是一个惴惴不安的罪人,一边等待原告的指控,一边焦虑地思考着“我做人怎么这么失败”?

门被推开了。经理在我对面坐了下来。他微笑着递给我一沓纸。我迅速扫了一眼标题文字:我做得很好,超出了预期目标!我突然松了口气,用了5秒钟的时间来放空自己,感受着这个瞬间——我做到了!我通过了考试!

第一页纸是对我的肯定,写着我的各种优势、以及同事们对我的好评,我草草翻过。

第二页纸写着我的提升空间。说白了就是没有达到业绩要求的项目、和我在工作中出现过的马虎和失误。

经理看出了我的心思,说:“你太在乎自己的不足之处了,其实真正能让你走得更远的是你的优势。”

“当然,你说的对,”我不走心地嘟囔了一嘴。

他的话我一个字都没有听进去。这一分钟里,我满脑子想的都是如何弥补欠缺,让自己表现得更好。

我始终没能明白他的这句话,直到好多年以后。

在一次教会活动上,我的妈妈了解到了一个让她心生羡慕的世界——数学夏令营。

唱完最后一首圣歌之后,一群妈妈们聚到一起。其中的一位妈妈滔滔不绝地讲起了她的女儿:她的女儿每年都会到外州去参加夏令营,一同参加的都是数学能力很高的孩子,这些孩子们聚到一起探讨着很高深的数学知识。

夏令营结束后,孩子们会不舍地告别彼此、各自回到家中。但他们不会就此断了联系,他们辗转于全国各地,追随着各种数学竞赛,说不定在哪场比赛上就会再次重逢。在座的妈妈们都叹了口气,她们想象着夏令营小屋里迸发的智慧、和颁奖典礼上奖牌碰撞发出的悦耳叮当声。

妈妈给我讲这些的时候,无奈地摇了摇头。“人家从10岁就开始了!”,她嚷嚷着。

我下意识地耸了耸肩。的确,我已经读高中了,我的数学还不错,但是似乎没有什么值得拿出来炫耀的成绩。我很向往妈妈提到的夏令营,和其他小伙伴一起过暑假听起来真有趣。

而我知道,妈妈的脑子里正想着完全不同的一些事情。

她从来都没有意识到,她的公式其实是有漏洞的,这个公式从来没有计算过错误的成本,一旦酿成错误,我需要付出的代价是什么?

5

高中毕业典礼上,我坐在第一排的第一个座位上。

坐在这个主座上,舞台上的一切都能尽收眼底。我戴着毕业帽,穿着一件皱皱巴巴、大得离谱的蓝色长袍,既兴奋又急切。我知道毕业是一件很了不起的事,意味着人生的这一段旅程即将画上句号。我知道父母和朋友们现在正坐在观众席中,近乎哽咽,看到我们终于迈入成年,他们的眼泪终于夺眶而出。我也在感受着每一分每一秒——等待进入会场、听校长讲话、意识到自己在这所学校的时间所剩无几,即将踏上通往未来的那艘船。

大概在此半年前,我收到了梦校的录取通知书。当时是春天,学校发来了为期三天的“准新生”周末体验活动的邀请。我独自一人坐上飞机,决定去看看大学的样子。在那里,我第一次跟素不相识的人聊了一整夜。从喜欢的电影,到未来的生活计划,我们随心所欲地说着各自的心里话。这种自由的感觉太刺激了——学长们谈论着下学期准备修什么课程,纠结着明天早餐吃华夫饼还是煎蛋卷,他们现在已经可以自己定义生活的公式了,真好。

我突然感到神清气爽,我好像第一次看到了有色彩的世界,恨不得马上飞奔而去,去抓住每一个瞬间,去以主角的身份重新开始一段故事。

你一定以为从此以后我就会跟变了个人似的——懒散地过完高中最后几个月,彻底摆脱对学习、分数的执念。

但是,当我坐在毕业典礼观众席的第一排第一个座位上时,我满脑子想的却都是,我为什么没有被选为上台发言的毕业生代表,我还是不够完美。

我并不是第一名。

我丈夫说过一句话,如果你对现在的生活感到满意,那说明你过去所做的决定都是正确的。

我却不以为然。我们聊过数十次这个话题。我说,“人都会犯错的,而且总是能从过去的错误中学到一些东西的。要是我早点知道现在所知道的东西的话,我肯定会换种做法来做某些事情。”

“比如说呢?”他接着问我。

“我肯定不会像以前那样度过大学四年。我肯定不会为了简历好看而去上那些我很讨厌的课,我一定会选一些我真正感兴趣的东西学。”

他笑了笑,说:“但我们俩就是在大学里认识的啊。如果你选的都是书法课这类‘鸡肋’课程,我们可能也就没有机会认识了。”

很难说服他,我明白。我知道他的意思——就算有机会重新来过,我也并没有改变过去的勇气。我看过那么多的旅行电影,自然明白蝴蝶轻轻一拍翅膀,世界的另一侧就可能爆发海啸。

但我还是反驳了他:“我的意思并不是改变过去,而是下次有机会的话我要改变!”

他翻了个白眼。说“难道还能有第二次上大学的机会吗?”

他知道我的意思。

回想起来,大学也是一个充满了条条框框的世界,它给我们的束缚远比现实世界多。四年里,我们还是需要没完没了地上课、参加活动,期中、期末考试丝毫不敢松懈,按部就班地朝着“毕业”努力。

但是现在,在硅谷工作了十多年以后,我终于知道,任何公式都是不可靠的。

把过去的假设用到未来总是会出现差错的,既然如此,又有什么完美可言呢?

千奇百怪的故事每天都在上演着。

有人押上了全部资产投资一个很有前景的项目,结果石沉大海;有人选了一个并不被看好的领域,却意外赚了一大笔。

有人在四年的时间里投入了全部心血、汗水、眼泪,结果一切化为乌有,有人提出了一个很好的策划方案,却足足等了两年时间才见到成效。

有人原本是个小混混,现在却在各种会议上作为主讲嘉宾侃侃而谈,而有人明明很出类拔萃,却常常为想不出新点子而焦虑不堪。

完美到底意味着什么?是社会影响力?是财富?是优雅的举止?是光鲜亮丽的穿着?是孩子、父母、丈夫崇拜的目光?是跻身知名人士的圈子?是社交平台的粉丝数量?是某篇文章的转发人数?是无忧无虑的生活、还是克服痛苦的毅力?是实现奢侈品自由?是保证自己潇洒过活的资本?是真切地感受到自己一直在进步、而没有退后?

一把尺子对应着一种完美。完美这种东西其实并不稀罕。

但是,没有人能够满足全部的完美标准。

我回头看看父母的美国梦。他们想要的是安稳、舒适的生活——我早就实现了这个梦,我得到的东西远比这些多。

但是我的梦是什么?

我做妈妈了,宝宝依在我的臂弯里。看着她纤细的睫毛、软软的小拳头,我恍惚了,真不敢相信自己竟然能把一个完整的小人儿带到这个世界上。

她的到来填补了我生活里的罅隙。但带孩子的日子其实并不好过,一日如一年。我的宇宙已经超负荷,我的心已经悄无声息地爆发了。

又到了喂奶的时间。我的身体轻轻地靠近她的小嘴巴,她本能地躲闪了一下,然后便开始咕哝咕哝地吮吸。原来为人母就是这样的画面。

我想到了我的妈妈和婆婆,她们都为我终于加入了母亲的队伍而感到高兴不已。

我从妈妈那里得知,我就是吃母乳长大的。母乳喂养在当时的中国还是一个新事物,医院推出了母乳喂养试行计划,我的妈妈加入到了其中。她告诉我,医院把所有婴儿都放在看护室里,每隔几个小时让母亲母乳喂一次,“我很紧张,不知道哪个是我的孩子,每次我都是等别的妈妈都找到了自己的孩子以后再去找你,没人认领的那个一定就是我的。还好,你越长越像我,我渐渐可以认出你了。”

我问她,为什么不让婴儿和妈妈在一起,就像我生完孩子后那样,转过头就能看见小宝宝躺在床边的摇篮车里?

妈妈回答说,“不不不,医院不是不让,他们只是希望妈妈们能多休息。”

我的婆婆也有一段相似的经历,她后面生的几个孩子都是母乳喂养长大的。她说:“老大出生的时候还不流行喂母乳。”“后来听说母乳很好,大家就都跟着学了起来。”

很难相信,不过几十年的时间,喂孩子这件事竟然会发生这么大的变化。

60年代的育儿常识显然已经行不通了。

多年以前,丈夫等在候诊室抽着烟,女人们在产房里照样分娩。而现在,这样的做法极可能对产妇造成生命危险。

多年以前,老人们都提倡婴儿趴着睡觉。而现在,这种姿势却成了婴儿猝死的元凶。

我们对复杂的人体知之甚少。而说到底,我们真正了解的东西又有多少呢?

完美的规则总是在变化着的。

几个月前,我买了一张蜂蜜色的柚木桌子放在家里的露台上。它的颜色太温暖了,就像夏天的阳光一样。但过了几个月以后,桌子变成了暗褐色,桌面布满了污渍和食物残渣——黄油玉米粒、三文鱼肉渣、和小坨的沙拉酱。

上周的某一天,从桌子旁边经过的时候,我翻了个白眼——桌上的污渍实在太难看了。我想,“我应该把它擦干净。”于是便开始在Youtube上看各种擦桌子小妙招的视频,又去亚马逊买了一些清洁用具。我觉得自己应该把这张柚木桌子拯救出来。

阳光真好,我终于动起手来。令我欣慰的是,几次擦拭过后,虽然我手里的刷子已经变成了煤烟色,但桌子上的暗褐色的斑点确实变浅了一些。“加油!”我在心里告诉自己别停下来。反复擦几次后,原来的蜂蜜色终于显现出来了。

但是污渍还是顽固地浸在里面。我改用更强力的刷子,开始专攻一块形状像墨西哥地图一样的深色污渍。所幸,它终于也渐渐褪去了。

但抬头一看,桌子的另一侧还有几块大的污渍。

我干劲十足——我觉得我可以把它们都解决掉。我有能力把过去留下的所有脏东西都清理干净,把它变回一张新桌子。我抻了抻胳膊,准备着下一轮清洁。

“妈妈,你在做什么?”女儿的小脸蛋从露台的门外探了出来。我居然都没有注意到已经过去了这么久的时间,女儿已经放学了。

“我正在打扫桌子,宝贝。”

可想而知,她对这个任务一点都不感兴趣。“妈妈,给你看看我今天画的这张画!”她自顾自地挥着手里的蓝色画纸,说。

我回头看了看那张斑驳的桌子,本想告诉她,妈妈再用二十分钟就可以擦好了。但话到嘴边又咽了回去。

“完美”应该是我们终其一生追求的崇高真理吗?它是不是一种控制的幻觉?蒙蔽了我们的双眼?

我脱掉手套,把刷子扔在角落里。

生活总会有污渍的。

但那也许就是完美的另一种形式。

The Curse of Perfect

In the house that I grew up in, there was a formula for the American Dream.

My parents believed this so deeply that they left China with a one-way plane ticket and hundreds of dollars in folded bills, their mouths full of broken English.

Here is how the formula went: learn English. Get the top marks in your class. Stay at least a grade level or two ahead on math and science. Enter and win academic competitions (science fair, math tournaments, etc). Ace the SATs. Become the valedictorian of your high school. Attend an Ivy League school. Study medicine or law. Afford a life of security and comfort.

The formula was not for my parents, who arrived to the game in the third quarter, too late to score a decisive victory. Their eventual middle class livelihood was built from the ground up waiting tables, losing sleep, and the continual habit of sacrifice.

But for me, my lips still loose enough to adopt perfect English, my eyes acute enough to observe and adopt the guise of American culture, it became my Gatsbian green light. My parents spoke of it with an unshakeable fervor. “Zhuo Li,” they’d point out to me every time we stopped at a red light and somebody tapped our window to see if we wanted to buy the day’s paper, “If you don’t study hard and get good grades, you too will have to sell newspapers on the street corner.”

In our circles, examples of children who had followed this formula to wild success were repeated like myths: “Auntie Wenfang’s daughter Sophia got a 1590 on her SATs and was just accepted into Harvard.” “The Tao’s son Frank did an internship at Dow Chemical lab and won first place at the science fair.” “Pam from church recently won a state piano award for her concerto performance.” Success was as uncomplicated as the times table — an unblemished report card; a Sunday dusting of the glittering trophy shelf that grew year over year; another line to add to the future resume that would transform into the entry card into the Promised Land of the Ivies.

In my parents’ mind, the concept of “perfect” existed. There was a right way to go about things. 99 was not as good as 100.

The American Dream, as I was taught, was less a spectrum than a binary switch.

I read Plato’s Dialogues in high school, and in it I was introduced to the concept of Forms. Instantly I was transfixed. In the book, Socrates suggests that for everything we can think of, tangible or not — dogs, grace, friendship — there is a true ideal form of that thing.

Yet the true ideal form is not something we mere mortals can behold. We are like prisoners tied down in a cave, a fire burning behind us as we stare straight ahead at the smooth grey walls. There, shadows dance — the outline of a dog wagging his tale, the dancing body of a ballerina, the swaying silhouettes of friends in song.

If this were all that the prisoners saw, would they not think the shadows were everything? That the dark shapes moving across the wall represented dogs, grace, and friendship in all their essence and beauty?

But no, we who are wiser, who are outside of the cave, who are a dimension apart, pity the cavemen. We see the real three-dimensional objects and know that they are so much more colorful, textured, and rich than shadows could ever be.

I could understand the allegory perfectly. It described my life: always in search of the brilliance of these Forms that I could never truly attain.

A worthy goal, surely? A foot, an inch, a nudge closer out of the cave and toward the true light.

I am sitting in a sunny conference room, my stomach fluttering. It is performance review season, and my manager is about to walk in and deliver my assessment.

I have sat in this chair every six months for the past few years, feeling this same cocktail of emotions: anticipation, dread, and expectation. I am equal parts Christmas kid — Will there be a strong review or promotion under the tree? — beaming cheerleader — Come on, Rah! Rah! You know you are awesome! — and nervous defendant waiting for the prosecution’s argument — in what ways have I failed as a person?

The door opens. My manager sits across from me. He is smiling. He hands me a sheet of paper. My eyes quickly skim the headline. I’ve done well — I’ve exceeded expectations. Relief floods through me. I allow myself 5 seconds to savor the feeling — I’ve done it! I’ve passed the test!

Then, I flip past the first page, barely giving a second glance toward my strengths or the nice things colleagues have said about me.

The second page is my quest. Here are all the things I could be doing better. Tallied here are the projects that weren’t up to par, the sloppy mistakes, and the blind spots.

My manager see this. “You’re always so eager to focus on your areas of growth, but I think you’re going to go farther with your strengths.”

“Of course,” I mutter.

But I am not hearing him. The message won’t sink in for another few years.

All I can think of at this time is how to build a better version of myself by ironing out what’s defective.

At a church event, among a cluster of mothers catching up after the last hymn is sung, my mom learned something that rocked her world.

It was the concept of math camp. She listened to another mother recount how her daughter spent weeks every summer out of state, in the woods somewhere, communing with a group of other precocious students over competitive math concepts.

After the camp was over and the students dispersed back to their homes, they would still see each other on the circuit — the network of math competitions that happened all over the country. The mothers sighed, imagining the aptitude in those cabins, the clink of medals during the award ceremonies.

My mother shook her head ruefully as she relayed this to me. “This starts at age 10!” she exclaimed.

I shrugged. I was already in high school. My math skills were fine but nothing to write home about. The part that sounded fun was the camp portion. I’d never spent weeks away from home with other students. But I knew my mother was thinking of something else.

Her formula was flawed. It hadn’t accounted for this. How much would the error cost?

At my high school graduation, I am seated in in the first row, in the first chair.

It’s a prime position with an amazing view of the stage, and I’m wearing my too-big crinkled blue robes and hat. The mood is equal parts festive and impatient. We know this milestone — graduation — is, like, a big deal. We know our parents and friends are in the audience, many working to dam the tears that will inevitably flow at seeing us cross this threshold into adulthood. Yet, we are also so over this — the waiting, the speeches, the still being here instead of having embarked already on that ship to our future lives.

Almost half a year ago, I received the fat acceptance letter to my top choice university. In the spring, I flew on a plane by myself for my first three day taste of university life at a “prospective freshmen” weekend. There, I pulled my first all-nighter talking about life and movies with people I’d never met before. The freedom was breathtaking — students just a few years ahead of me waxing about what to study next year, whether they wanted waffles or omelets for breakfast, creating their own formulas for the rest of their lives.

I felt suddenly awake, like Dorothy seeing color for the first time. I could go out and spread my arms, grasp the infinite, step into being the protagonist at the true start of my story.

You would have thought that this meant I’d return changed. That I could have sailed through the rest of my months in high school. That I could have eased off from the studying, the fanatic desire for the flawless scores.

But the prevailing thought in my mind as I sit in that first row, in that first chair, is that I am not up on stage, where the valedictorian and salutatorian sit, waiting to give their speeches.

I am number three.

My husband has a saying that if you’re satisfied with your life today, then every decision you’ve made in the past is a good one.

I disagree. We’ve had this conversation dozens of times. You can always learn something from your past mistakes, I say. And knowing what I know now, I’d do so many things differently.

Like what? he asks.

I would have had a completely different college experience. Taken more classes I was genuinely interested in instead of optimizing for my resume.

He grins. But we met in college. And if you’d been taking calligraphy or underwater basket weaving, maybe wouldn’t have the relationship we have now.

It’s hard to argue with that. And I know what he means — I wouldn’t change any part of the past even if I had the opportunity to. I’ve watched enough time travel movies to know that if you help more butterflies flap their wings, you might start a tsunami on the side of the world.

But I find an opening anyway. It’s not about changing the past. It’s about doing it differently the next time.

He rolls his eyes. The next time you do college?

He knows what I mean.

Looking back, even college felt structured and formulaic against the real world. After all, we still had the sturdy drumbeats of midterms and finals, the steady climb towards “graduation,” the finite set of classes and clubs.

But working over a decade in Silicon Valley has taught us that formulas are unreliable.

How can anything be perfect when the assumptions of the past are so often wrong in predicting the future?

How can you believe you have control when, depending on whether you were at the right place at the right time, fortune smiles and bestows upon you green light after green light to wealth, prestige and power?

Every day, there are examples. This investment went to zero. This other one multiplied like bunnies. These four years of blood, sweat and tears crumpled into nothing. This idea took two years to change an industry. This asshole guy you knew is suddenly the keynote speaker at every conference. This brilliant friend is struggling to get momentum for her next new idea.

But really, what does perfect even mean? Is it impact, is it wealth, is it having the right manners or the right clothes? Is it the adoration of your children or your parents or your spouse? Is it being liked or talked about in the right circles? Is it the number of followers or retweets? Is it the lack of suffering, or the overcoming of suffering, or the act of suffering nobly? Is it your capacity to savor the luxury of individual moments? Is it simply the feeling that you are going up instead of down?

On every metric, there are those above and below you. Examples are a dime a dozen.

I look back at my parents’ American Dream. Security and comfort. I have reached it, and more.

But what is mine?

I am a new mother, my first child curled into the crook of my arm. I marvel at her tiny eyelashes and fists, scarcely believing I have helped bring to life a full, perfect human being.

The days have blurred together. It’s been only a few weeks, but it has felt like a year. My universe has expanded, supernovas exploding silently in my heart. The quiet moments stretch out as delicate as the spaces between a spider’s web.

It’s time to breastfeed. My baby grunts and roots as I gently nudge her into position, wincing as she first latches on before relaxing as she gets into a steady suck. I’m thinking about my mother and mother-in-law, who have both welcomed me into the moms club with stories of their own journeys.

I had asked them if they breastfed.

My mother said she did, but it was a new concept at the time in China. She was part of an experimental group of mothers encouraged to try a new process at the hospital. The babies from their ward would all get wheeled in every few hours to be breastfed. “I was so nervous,” she told me. “I couldn’t tell which one was my baby, so I’d wait until all the other moms picked up theirs first and assumed the remaining one was mine. Thankfully, you turned out to look like me, so that’s how I know I hadn’t messed up.”

I asked her why the babies weren’t with the moms. After I gave birth, the hospital kept her in a little bassinet right next to me.

“Oh no,” my mother said. “That wasn’t the protocol. They wanted the mother to get plenty of rest.”

My mother-in-law had a similar story. She didn’t breastfeed her older kids, but did with her younger. “It just wasn’t the thing back when I had my first,” she said. “The prevailing wisdom was that formula was better. Then, suddenly, breastfeeding became the recommended thing.”

I reflect on the differences in new motherhood in just a few decades. How back then, the men stayed in the hospital waiting rooms during labor, smoking their cigarettes which we now know to kill you. How babies were advised to sleep on their stomachs, which today we’ve associated with a higher risk of sudden infant death syndrome. How immediate skin-to-skin contact for newborns was deemed less important than it is now.

Imagine if you had been following all the rules perfectly as a new mother in the 1960s.

How little we knew of the complexities of the human body. How little we know still of all that we don’t yet know.

The thing is, the rules of perfect are always changing.

I purchased a teak table earlier this year for my patio, loving the warm honey color that reminded me of the long rays of summer. A season later, the surface was a dull brown and riddled with stains, remnants of dinners involving buttered corn and grilled salmon and dollops of tartar sauce.

Last week, I grimaced when I saw the table, the stains like a patch of disease. Of course I can fix this, I thought. A few Youtube videos and Amazon purchases later, I felt like a warrior-sage of teak, armed with speciality cleaners to battle the stains.

The sun was high in the sky. I scrubbed the table with the cleaner, and to my delight, the dull brown lightened a few shades. My brush was the color of soot. Go me! Energized, I did a second round, then a third. The honey tones began revealing themselves.

But the stains persisted. I switched to a stronger brush and attacked a particularly egregious dark patch shaped like New Mexico. I put all my weight into the most vigorous scrub I could muster. To my satisfaction, I could see it weakening. I doubled down, slashing the bristles back and forth. A few minutes later, huffing, I stepped back. The stain had disappeared! One dragon down.

Across the table, there were dozens more. I felt a giddy satisfaction. I could tackle all of these. I could make the table like new, erase all these past accidents. I stretched my back and readied myself.

“Mommy, what are you doing?” My daughter’s face peeked out from the patio door. I hadn’t noticed that the sun had scooted across the sky, and now she was home from school.

“I’m cleaning the table, Baby.”

She couldn’t be less interested in my battle, the one I am poised to win. “Let me show you this drawing I did today!” she said waving a large blue piece of construction paper.

I looked back at my spotted table. Twenty more minutes was all I needed. I opened my mouth to tell her, then paused.

Is perfect a noble truth we pursue, or an illusion of control that blinds us?

I peel off my gloves and throw my weapons in the corner.

Life will always have stains.

Maybe it’s just about trading one kind of perfect for another.

【编者按】本文仅代表作者观点,不代表APAPA Ohio及OCAA官方立场。所有图片均由作者提供或来自网络。如存在版权问题,请与我们联系。更多精彩文章,请查看我们公众号的主页。欢迎大家积极投稿!

【近期文章】

关于俄州亚太联盟公众号

俄州亚太联盟公众号是APAPA Ohio在俄亥俄华人协会(OCAA)的支持下办的公众号,旨在为俄亥俄的亚裔群体、尤其是华人群体提供一个分享、交流、互助的平台,宣传APAPA Ohio 、OCAA和其他亚裔团体的活动,促进亚裔社区对美国社会、政治、文化、教育、法律等的了解。APAPA的全名是Asian Pacific Islander American Public Affairs Association (美国亚太联盟),是在美国联邦政府注册的501(c)(3)非营利组织。网址:APAPA.org

最新评论

推荐文章

作者最新文章

你可能感兴趣的文章

Copyright Disclaimer: The copyright of contents (including texts, images, videos and audios) posted above belong to the User who shared or the third-party website which the User shared from. If you found your copyright have been infringed, please send a DMCA takedown notice to [email protected]. For more detail of the source, please click on the button "Read Original Post" below. For other communications, please send to [email protected].

版权声明:以上内容为用户推荐收藏至CareerEngine平台,其内容(含文字、图片、视频、音频等)及知识版权均属用户或用户转发自的第三方网站,如涉嫌侵权,请通知[email protected]进行信息删除。如需查看信息来源,请点击“查看原文”。如需洽谈其它事宜,请联系[email protected]。

版权声明:以上内容为用户推荐收藏至CareerEngine平台,其内容(含文字、图片、视频、音频等)及知识版权均属用户或用户转发自的第三方网站,如涉嫌侵权,请通知[email protected]进行信息删除。如需查看信息来源,请点击“查看原文”。如需洽谈其它事宜,请联系[email protected]。