当医生自己成为癌症患者时: 宣战与收获(感人至深/ 中英文)

【留美学子】 的读者文摘

第 845 期 只精选好文 不链接任何广告

仰望星空、脚踏实地

【陈屹视线】导语:

感恩【留美学子】平台上的三位特约作者赐予本人三次机会,

让我走进了美国医生的世界,而且他们都不是普通的医生,而是神经、心脏相关的外科手术专科医生。

文章是被反反复复编辑出来的,连续数周,自己含着泪水品读着他们的文字,在照片中,对话他们的灵魂!

感动于他们字里行间,不仅浸透着学医、从医一路走来的艰辛,更触摸着他们笔下展现的:

这么艰难学医、

这么艰难经历住院医生的训练、

更加这么艰难的成为医生,

当“好日子”终于降临之时,

却发现.......

当医生自己成为癌症患者,

不得直面生命挑战,

他们内心也曾出现惊慌、不安,

......

然后,

再内心的强大和毅力。

人生路上的风云变幻,

带给与患者同舟共济的医生们

重新审视世界、

审视治病救人的选择、

审视何谓爱和生命的意义和价值!

这一切一切令人对医生们崇高的事业,

更加肃然起敬!

谨此献上我们的敬意、致敬与深深的鞠躬!

感恩三位作者,

感谢这些超越时空的人生告白!

(已经发表的另外两篇文章,

【朋友相互推荐的一本美国畅销书】

【为何美国学医从医如此"艰难", 医生妻子眼中的"真实世界"】)

在此文结尾处有链接。)

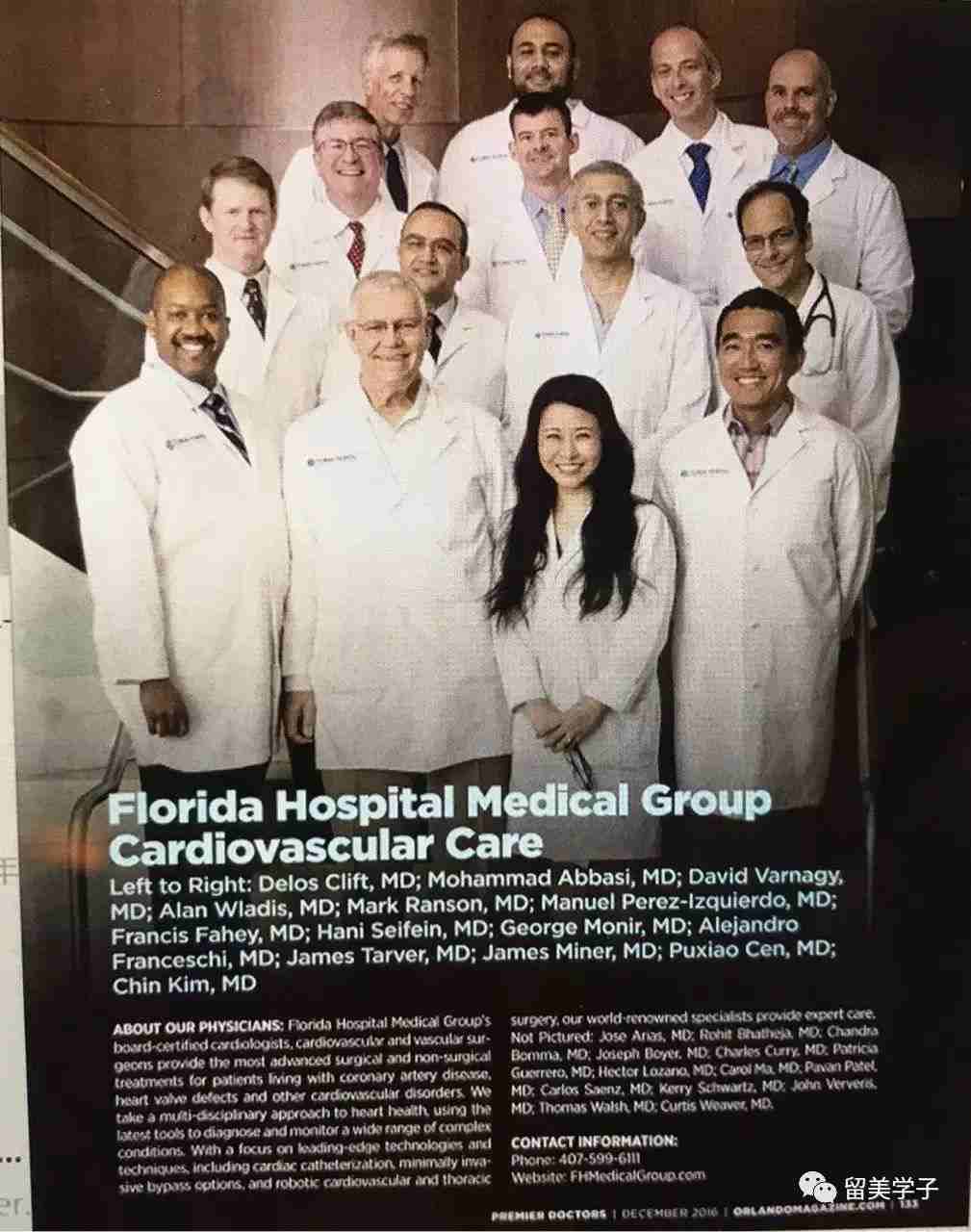

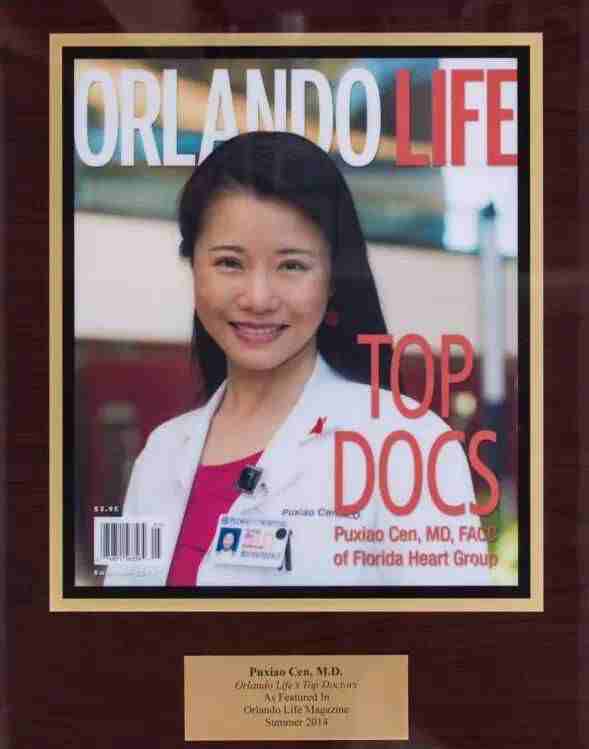

本文为岑瀑啸医生的自叙,作者系美国佛罗里达医院心血管专科医生她以自己从一个医生变为癌症病患的亲身经历,与我们分享她在角色转换过程中的躯体体验和心路历程。

她希望本文对于从事医务工作的读者有所启发或帮助,也希望与非从事医务工作的读者由此明白,医生也像平常人一样,当他没有亲身经历过一些事情的时候,他的某些看法难免有其局限性。因此,我们每个人都不妨多一些怜悯和谅解的情怀。

岑瀑嘯与她的生活伴侣赵崇尚的对话来自 【佛山电视台】采访时记录。

赵崇尚

岑瀑嘯

赵崇尚

岑瀑嘯

:什么是你会原谅的?

岑瀑嘯

:人都会在某些时候变得脆弱。

赵崇尚

:你事业上的遗憾是什么?

岑瀑嘯

: 我工作中没有不安全感,但人生多次在事业的选择上, 因为我缺乏自信,于是放弃了一些机会。

赵崇尚

岑瀑嘯

赵崇尚

岑瀑嘯

赵崇尚

岑瀑嘯

赵崇尚

岑瀑嘯

:在你生命中最遗憾的是什么?

岑瀑嘯

:没有机会和我爸爸说“再见”。

赵崇尚

:你仍在追求的目标是什么?

岑瀑嘯

:更加关心在乎爱我的人,

赵崇尚

:你的动力来自哪里?

岑瀑嘯

:去履行我的任务,实现 ”我再给予“的目标。

赵崇尚

:你最珍惜的快乐是什么?

岑瀑嘯

:让爱我的人快乐。

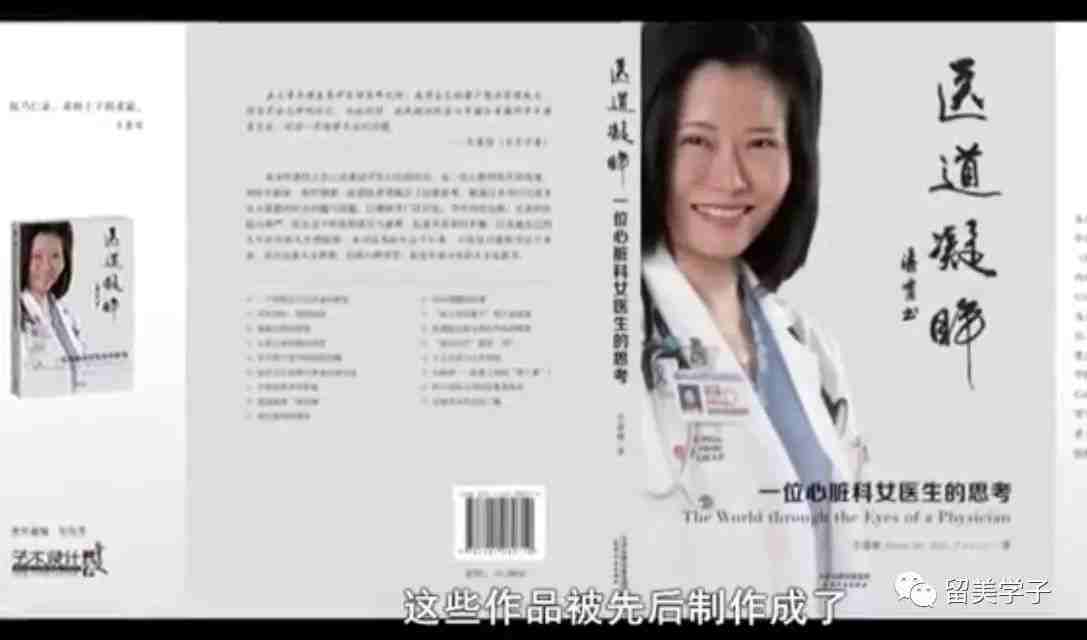

没有来得及与父亲道别,父亲去世后的三年,除了繁忙的工作之外,作者就是伏案疾书,写下对生命的热爱与思索。

2007年夏天,我被确诊罹患卵巢癌盆腔转移,后来历经几年,经手术及化疗最终治愈。本文为首次将自己作为病人的经历分享给大家。

首先我感恩自己生于现代医学发达的时代,能及早发现癌症并获得有效的治疗且愈后至今良好。我展望未来的时候,看到更加早期发现癌症以及增加个体化地治疗的必要性,在进一步提升治愈率的同时尽量减少对病人生活品质的损害。我自认一向身体强壮,首次亲身经历现代医学的神奇;同时体会到疾病和治疗带来的痛苦。生病是一个孤独的过程,无论有多少爱你的人为你打气。做了那麽多年的医生,尽管我常常提醒自己要将心比心,易地而思,还是不及从自己患病所得的体验深刻。

当一个疾病不是像感冒那样时间较短,患者的斗志和自信会有起伏。而在与家人及医疗人员相处的过程中,因为希望做一个容易相处的人,病人也会出奇地担任了一部份照顾人的角色。当我忍受一波又一波的恶心和呕吐、腹泻、肚子绞痛、发高烧的寒战、退烧时候的大汗等等,难免会为自己的无能和身体的脆弱给人带来的不便感到内疚。

当我刚得悉自己罹患癌症时,我的头脑还处于往昔的“医生状态”,反而没有那种我所观察到的病人惊愕、恐惧或伤心。所感受的只是希望可以多了解一点这类型的癌症,心里想著哪一种肿瘤杂志我会在见完医生后去搜索,甚至觉得自己的临床和教学方面每星期、每月的计划不会中止或变动。

可能是这种测量自己的影像、病理报告,搜索医学文献,去研究自己的疾病,是一种隔绝震惊的形式;它又刚好属于我的本行最熟悉的动作和行事,所以突然听到噩耗时我就不由自主地条件反射似的,将自己的思维转作一种学习和研究的形式。

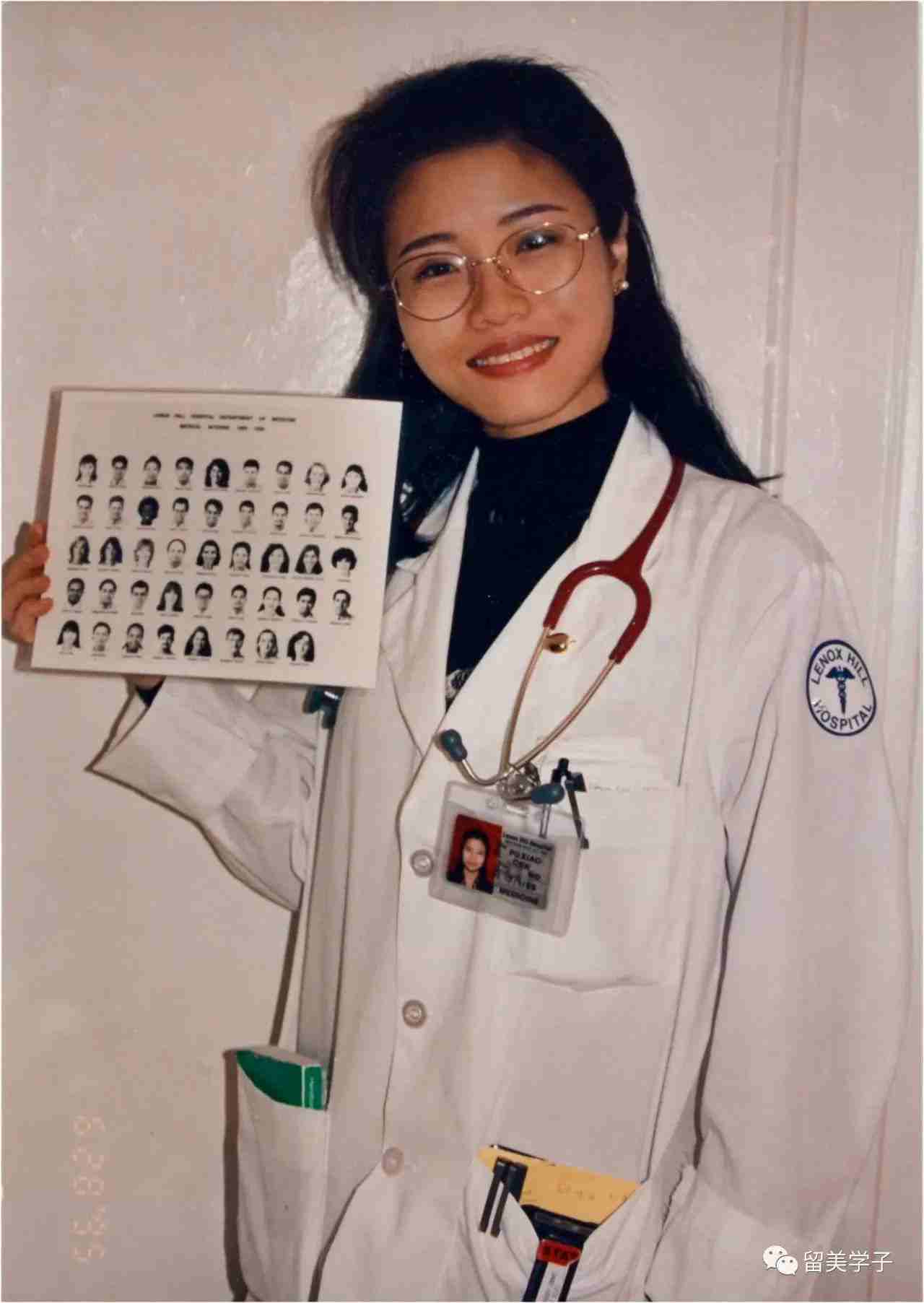

1995年在纽约的 Lenox Hill 医院 做内科住院医生时

此过程让我理解了为什麽一些病人在心血管病非常严重时,锲而不捨地钻牛角尖,要求我解答许多我认为对疾病大方向的治疗无关痛痒的细节;有的病人会经常在每次复诊前在网上列印很多资料,捅来和我讨论,“听我的意见”,其实只是令他的心得到一些安慰;而我经常觉得这种执著是浪费时间,我难以理解这种不懂得抓重点的行为。等到自己也做同样的事时我就明白,这种好像“糊涂”的举措是为了努力一种假像,仿佛自己还有能力掌控大局,以免陷于恐惧。这个假像就包含不断学习、研究、寻找答案的形式。

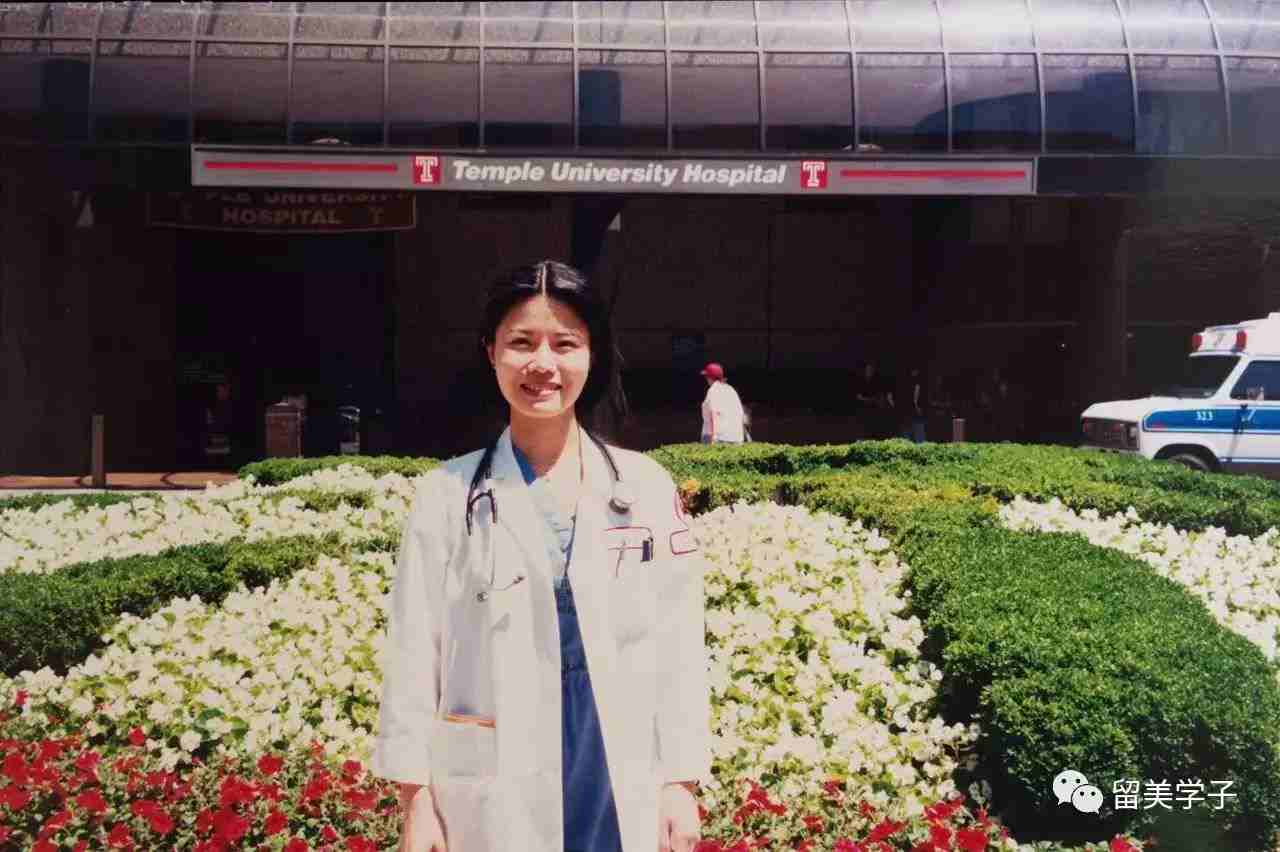

1998年 在 Temple 大学医院

我的同事非常体贴,知道了消息马上开始帮我照顾我的所有病人,让我专心休息。我任职所在的心脏科在我接受治疗不能上班的过程中,继续发工资给我。但我还是答称不要紧,以为我是不可能病到不能工作的地步。即使不能维持原有工作量,或可减少工作量、病人的数量,或可在幕后通过看病人的结果,和电话上继续免费解答他们的疑难。而后者(电话谘询)已是每个医生的日常事务。我觉得自己还可继续做。

如此无视问题的严重性,坚持工作,其实也是不愿面对残酷现实的一个反应。

做了手术我才躺在床上完成了自己的角色转换--我不再是指导这个疾病的治疗的医生,而是一个身体上有病的人。在此之前每次我和我的医生探讨病情,我站在旁边就像是他的同事,一起讨论一个第三者的病理报告和身体影像的结果,看上去好像是一个最镇静、最合作的病人,其实也是一个最否认现实的人。

作为病人,我也经历过标准化医疗手段带来的不快。例如当我化疗后白细胞减少,不同的感染都少不了新一轮的X光胸片,抽血做细菌、真菌和病毒的培养,而且多是正值我难以有足够睡眠的情况(因肠胃不适的和高烧、发冷等而致),还因护士定时检测我的体温,发现我体温升高便亮灯为我抽血,用床或轮椅把我带去放射科;如我太软弱无力则由放射科工作人员前来为我照胸片,这些都使我本已软弱如麵条的身体备受折腾。

尽管我心里明白这些都是重要的步骤,是医生不希望失去捕捉到细菌、病毒和真菌的机会。只有捕捉到这些病原体资料,他们才可以有的放矢地调整抗病毒和抗菌的药物。

当我手术后伤口的疼痛令我受皮肉之苦时,也感恩能有一个装有微型电脑的自行控制的止痛静脉注射器(Patient Control Analgesia,PCA)。它其实不是新技术,但此次我切身体会到给病人一个自我控制的机会是何等重要。病人无须等到疼痛难忍时才按铃召唤护士,为己作止痛注射。因为无论护士来得多快,总有一段时间让病人继续忍受痛苦。何况当时未必有护士可以即时自其正在执勤的地方脱身前来。

这种自我掌握命运的感觉很宝贵,自然PCA的预设止痛药剂量有一定上限,病人不能多次按掣。因为不少止痛剂是吗啡或其衍生物,剂量太大可能会抑制呼吸。

我另一个感受就是,医学固然并非精确的科学,通常我们对预后的估计和一个治疗手段效果的估计,只是有一个数字附带上去的估计,也就是一个统计上的可能性。病人经常(差不多是常规性)的问题是,这个病严重不严重,或这个治疗有无副作用,每天听到很多次这种问题,有时我的第一反应是:我很难给你“是”或“否”的答案:有百分之几的可能会达到预期效果,成功的定义是什么;这种副作用或那种并发的几率;至于严重与否,取决于你对疾病的认识和我们治疗过程中效果的动态评定。

这些说法确实很科学,但同时也是令患者不安的答案。当然,我看来严谨的回答是一个职业化的表现,不是光说病人想听的;但当自己是病人时我就突然觉得,这些数字和计算之后的回答,对于身患重病、面对重大医疗选择的病人来说,蕴含著一种令人失望的冷漠。

诚然,医生主要职责是治病救人,尽力使之康复。能够安抚其心情,解除他的思想包袱当然很好,却未必可以做到。于是,病人难免因得不到安慰而沮丧,通常他不会因为认识到该答案的客观性而对答话的医生有所体谅,可能心里认为对方仅仅以事论事,一味“公事公办”,做交易一般。

这回我成了病人才真切地明白:医疗的过程重在客观地评定患者的病况并给予科学性的治疗,这样,有时情感上的安慰是难以兼顾的。或者可以说会是鱼与熊掌二者不可兼得。身为医生应时刻谨记这种局限性,有时变身为一个心理辅导人员给患者以温柔的心灵上的安抚。

所谓“医者父母心”,“情”岂非题中应有之义?

过去我认为病人照CT (电脑断层扫描) 是很简易的一个过程,无非是在静脉上注入摄影剂,病人躺在CT机上照一照罢了(我觉得唯一需要注意的是病人受到的放射剂量)。这回我自己做CT,才感受到静脉注射特别是口服造影剂时是难受的。吞服跟钡餐相似的流剂绝非乐事。此举旨在把造影剂输入胃肠道,以便使CT所提供的资讯更具临床意义。尽管“餐单”包括草莓味、香蕉味或苹果味(我全都尝试过),即使口味调制得与水果原味再如何相近,当我意识到此非食物,要一口一口吞下去,直至把一大瓶吃完,还是挺不容易的。再者,躺在CT机那又硬又冷的床上时,当我不知道此次造影结果会是如何,也就是我的癌症是否已经得到控制,有无复发,等等,为此而忐忑不安,我就会顿时觉得这个机器和技术员在话筒中告诉我的,似乎隐藏著一些我所不晓得的东西,处于一个战壕我的敌对方(就仿佛机器是我的对手一样)。

由此我首次感受到,以往听到的病人所云“你们医生”之类的说法是他感到没有一个人能看到他的痛楚或恐慌,当人觉得无助时将世界看成非黑即白,非我即敌的思维,份属自然。

在我的人生经历中第一次觉得我的生命由两股力量牵拉,一股是我的疾病,另一股是努力将这疾病去除的那一队人。而我似乎处于完全被动、无能为力的状态。因生病令我更谦虚。以往尽管我对病人及家属的建议纯属建议,但他们听起来可能会觉得(或我讲话时实质上)已经含有一种傲慢,起码是“自以为是”。我是假设自己知道什麽是对他们最有利的,有时病人和家属确实不知道何种选择于全局最好,而只知不同的选择可能带来短期的好处和坏处。事实上,他们往往需要一段(长短不一的)时间去探讨,或者此探讨的形式令医者觉得他们似乎对你不信任,老是重重複複的质问,而身为医务人员在有限的时间表之下,确实会觉得这种来来去去的质疑是病人的不友善,或其蒙昧无知的表现;医者会认为自己已经解说得很清楚,事实就是事实,而医学有时也并非那麽複杂深奥,为何他们怎麽也不明白,或者毫无必要地将一件相对简单的事情複杂化?

我现在才体会到,当一个病人或家属觉得他在疾病治疗过程中没有参与权的话,那种无助就会令其对治疗疾病的这队人都难以视为自己的团队,他觉得自己不属于任何力量,而只是一个被动的成分。要使之感到他是在医护人员这一队里一起并肩作战,这不是一次门诊15分钟的见面或一次查房便可达到的。成了病人的我首次体认到上述现象的存在。

虽然我以前也对病人在我接受培训时的作用心存感激,现在更加深了这种感谢之忱。因为我每次见到新的医生(手术医生或新参与会诊的各科医生),或入院见新的主管医生等等,我作为病人提供的自我病史基本上就如以往工作时我对着话筒直接口述,再由电脑自行打出来的一份病史那般精确完整,比如发病过程、诊疗方法、已接受过的治疗和效果等,我基本上像一个医生跟另一医生说话那样言简意赅。但当有正在受训练的住院医生来问其主管医生先前病史时,他们一次又一次问我一些其他的症状,有无喉咙痛、抽筋等,这些我觉得与我现在的病毫不相干的、或我个人认为对我毫无帮助的问题,我都要一次次地回答,于是我意识到每一代医生训练的过程,其实就是无数病人耐心地为之提供协助的一个过程;也就是说,医生受训时病人不光是接受其服务,而且提供了一个教学的机会,即也提供了服务。换句话说,我感受到一个病人无形中肩负的所谓“教学任务”其实也很繁重。

我两次的卵巢癌手术都是在我身为肿瘤专科医生的妹妹所工作的癌症中心做的。我住在佛罗里达奥兰多,妹妹在德州休斯顿。我之所以选择到那里,首先是由于我信任妹妹的专业水准,而她为我找的一位手术医生是她最信任的;其次是我希望在另一个地方住院和治疗(包括术后的恢复),可以令我得到更好的休息。

因为我在佛罗里达医院任职多年,认识的人很多,我在确诊和停止工作后,很快医院里不少医务人员都得到消息,有些病人知道被转去我的同事那里继续治疗,他们都纷纷热情致意,短时间内我收到600多份问候卡。如果我留在本地,将会有许多热心的同事和朋友前来探访,我或许不能得到更好的休息。而且我也不希望让同事见到治疗的过程。

在妹妹的照顾下,手术和术后恢复都非常顺利,当然因为离开自己的居住地和自己熟悉的医院,到另一个地方诊治(作为一个医生以往的小病、小检查都是自己的同事处理,不会有陌生的感觉),所以我第一次体验到:一个病人在自己最忧心时,把重要的决定权和信任都放在自己素未谋面的陌生人手上那种感觉。

虽然在美国这个专业管理比较严格的国家,医生和医院的品质都不会相差得太远;但信赖首次见面的陌生人为自己开刀,又相信同样是首次见面的麻醉师(会将自己手术中和术后的痛苦降到最低限度),等等,这些信任是我以病人之身,第一次赋予。而且我是临床上独当一面多年的人,面临需要将自己的生命交给自己不熟悉的同行,有一种感到突而其来的不安。

有句半玩笑的话说,“好的临床判断哪裡来的呢?是经验来的,但从哪裡得到经验呢?是从坏的临床判断。”也就是通过做错决定吸取教训而得的经验,是形成好的临床判断的基础。正因为医生知道这个错误的决定对病人带来的是什麽后果,所以我作为病人就很担心这个现实。

通过术后的康复和每一轮化疗身体为下轮化疗作的准备,我也体会到身体本身的健康素质之重要性。因为我从小经过游泳训练,在父亲的指导和鼓励下我在中学和大学都参加游泳队,参加过省级游泳比赛,体质潜力较好,术后恢复期对化疗所引起的对身体的负面影响消除较快。我病后格外感激父母对我小时强调锻炼身体之重要性,不仅要我读好书,专心学到知识和掌握学习方法,还要攒足身体健康的本钱,以便终身受用。这是多麽的有远见。

成了病人我第一次切身体会到,尽管医学经过多年发展取得长足进步,但毕竟还是年轻的科学,有许多不足之处。即使基于最好的初衷和动机,医务人员所做的决定和行为都未必尽如人意,甚至可能出现难以预料的不良后果。我第一次体会此种落在自己身上的可能性,果真如此,则不再是科学和客观地分析、量化方面的或然率问题,它对我本人不是百分之多少,而是残酷的百分之百。奇怪的是,一个人经历疾病时会更加意识到身体内的一股生命力。

平时身体无恙是一个谦虚的无言的帮手,帮我们实现脑袋中之所想。但当我病时就会格外分明地觉得自己是一个活著的生物,不仅是一个意识。例如我化疗期间,有时一早起来看到镜子中一个很消瘦的人,眼圈黑了、光头、面容苍白甚至有点近似灰黄的一个人在回望我,有点像《红楼梦》中的刘姥姥,头一次在贾宝玉所居的怡红院中照镜的感觉。在我身体承受手术后的疼痛和面对化疗期间的副作用时,由于本来任职医生,躯壳内仍存的“医生”完全明白这现实的必然性;但作为“病人”我就总是“不服气”,觉得自己被一个失去正常功能的身体束缚住。但在吃惊的同时我强烈地意识到,这个躯壳里面是一个很强的生命,在继续其未完成的各种运作;也就是说虽处罹患恶疾、生命最脆弱时,我反而第一次看到生命的力量,那是令我非常佩服的力量。

作者1998年摄于美国 Temple University Hospital

而正是因为意识到生命的强大,当我接受第二次手术时,躺在床上被推进手术室,在走廊不知转了几个圈,我望著天花板一格一格、灯一盏一盏地飞过,到手术室内只是看到很亮的无影灯,刺著双眼,那时第一次体会到“放手”的意思,把所有的控制权、主动权放出来,交了出去的那种感觉。当一个人身患可能致命的疾病如癌症,且需经多次治疗,对其接受治疗的日子会有两种相互矛盾的看法:一是这段时间乃一种奖励,因为如果不是接受治疗,这些日子可能不存在;但另一方面,这也意味著失去部份生命:此期间不能如常地生活,不能做自己以为有意义的、可以发挥主观能动性的事,而是只能被动地接受疗程。

我想,这种感觉不仅是癌症病人,可能是所有慢性病患者都会有的,并且需要学会去接受的。许多医疗手段往往在救死扶伤的同时,增加了伤患者的痛苦,是把他今天的生活品质去换取一个承诺--那就是希望可以活久一点,以及跨过这个困难之后的日子品质会比不接受治疗为佳。

这就是我觉得现代医学,或单纯说是医学对疾病治疗所造成的一种具两面性的效果。而有时为了在心理上接受这个矛盾性,病人会埋头学习有关自己疾病的知识,学习的细节可能已经到了妨碍他理解全局的程度。以往我会认为他们是过分执著,会反复告之曰:你无需知道更多细节,或这些细节不重要,让我替你操心即可,你最好自己尽可能设法活得好一点、潇洒一点;但现在我认识到,我这麽说或许是需要的,另一方面也不能期待我的话会改变他们的心情--因为他们力求掌握更多的有关资讯及治疗方式是很自然的。

我的化疗本来是6个疗程,但后来变为7个,因为其中一个疗程中有种药物在静脉滴注射时,突然导致我发生严重低血压和心律减慢,当时迅即晕了过去。记得那瞬间脑海中闪过“我要死了”的感觉。幸好医务人员行动快,抢救及时,尚无大碍。为此改变了后面一个疗程的成分,增加了一个疗程。

自从这次血压和心跳低到几乎丧命(那是在我自己的医院进行化疗的),我每次走过诊疗室见到抢救车(Crash Cart)都有所感触,觉得它离我很近。抢救车Crash Cart是每个诊所必备的一种铁皮四轮车,高约及腰,宽约一臂,设置许多铁皮抽屉,分别装著不同的急救药、注射器和气管插管的器材等,当病人突然出现生命体征的崩塌,可立即推到病人身边抢救。

以往我当医生时,它在我眼中像是一张凳子或桌子,不用时和家私没有什麽两样;但当我成了病人,它的存在就使我感到生命的脆弱,因为可能要在我身上用到这些器械。可见一个医生和一个病人,对医院或诊所中的同一设备是有不同的观察角度的,它所起的作用可有天壤之别。医务人员不用它时只不过放在那里,是房间里诸多物品和设备其中的一个;但就病人而言,特别是用过它的那些病人见到它,虽未必心有馀悸,起码会意识到自己身体恶化的可能性是很真实的,看得见摸得着的。

我生病后的另一收获就是,以往当病人面对坏消息时一时感情上接受不了,我可能会握住他的手说,我明白你的感受;但我病后不再这样说,改为:虽然我不可能、不可以或未做到完全知道你现在的感受,但会尽量去理解你的感受。也就是说,我在温言抚慰乍闻恶耗的病人时,不再自以为是地认定自己明白别人怎么想,情感的波动有多大。

以上零碎地谈了我作为病人的一些感受。这也是我首次在文章中忆述自己罹患卵巢癌,经过两次手术及7轮化疗期间的心路历程,和我学到从病人的角度去看疾病心得。我希望本文对于从事医务工作的读者有所启发或帮助,也希望与非从事医务工作的读者由此明白,医生也像平常人一样,当他没有亲身经历过一些事情的时候,他的某些看法难免有其局限性。因此,我们每个人都不妨多一些怜悯和谅解的情怀。

人生在世,不乏三灾六难五劳七伤,其中生病尤其寻常,其间特别需要别人的关怀,包括精神上的安抚和物质上的支持。后者往往受到经济条件的限制,而前者却只需一颗善心。

WHAT MY CANCER TAUGHT ME: OVERCOMING AND LEARNING FROM OVARIAN CANCER

Dr. Puxiao Cen shared her impressive story of ovarian cancer diagnosis, treatment and recovery with Baylor University Medical Center's quarterly magazine, Proceedings. Dr. Cen explains how her cancer diagnosis helped her to better understand her patients and grow as a physician. Read her story, originally featured in volume 28, number 4 of the Baylor Health Care System’s prestigious peer-reviewed journal, below.

What My Cancer Taught Me

In the summer of 2007, I was diagnosed with stage II ovarian cancer with metastatic lesions on the bladder. After two surgeries and seven rounds of chemotherapy, I am in remission and have undergone transformational changes from the experience. Fortunately, we live in a time of advanced medical development that allowed for early detection and effective treatment of the cancer—for which I will be eternally grateful. While this has given me a very good prognosis, it did not make the process any easier, despite the unflagging support of family and friends. I learned that no matter how much you are loved, being ill is a lonely journey.

The vast majority of illnesses most people experience are acute in onset, self-limiting, and relatively short-lived, like the common cold. However, with a chronic illness like cancer, where there is a long, drawn out, constant fight against the disease, individuals experience fluctuations of confidence and the will to fight. Not only that, but due to the protracted nature of the disease, they inevitably harbor feelings of guilt for being a burden to loved ones. Consequently, they try to be a “good patient” and not tell anyone, caregivers and doctors alike, about the physical and mental suffering they experience.

Maintaining Control

When I first learned of the diagnosis, I approached it from the role of a physician, which made it extremely difficult to experience the fear or sadness often observed in patients with similarly serious verdicts. When I read the pathology report, I was solely focused on the hard data about the clear cell carcinoma that I was found to have. My clinical mindset led me to spend a vast amount of time online learning about the latest research, just like I do for my medical practice. For all intents and purposes, I felt that my daily routine was not going to be disturbed by the cancer.

Looking back, I realize this thorough studying of my computed tomography (CT) and positron emission tomography (PET) images, pathology reports, and literature research was a way for me to insulate myself from the shock of the bad news. Because the mind spends much of its time trying to defy change, seeking an unstressed state, I fell back to the comfort of doing what I know well. By reflexively studying the science behind the diagnosis, I was helping to shield myself from the emotional impact.

This experience helped me better understand why some patients spend a tremendous amount of time and energy studying even the most minute details of each differential diagnosis. They even print out the information from their online search and bring it to the office visit to discuss with me. In the past, sometimes I was confused by such behavior, which I considered a refusal to accept the medical “truth.” I would say something like, “Relax; it is not as complicated as you think,” or “Don't worry; let me take care of you.” My patients' reactions would even make me feel untrusted. Of course, only after behaving the same way, obsessed about information on my own illness, did I understand my patients' insistence on knowing “everything” as a way to gain a sense of control.

The need to maintain control over one's life and pretend that nothing has changed can be pervasive. Even when my colleagues were kind enough to take over my workload so I could take time off, I continued to use electronic medical records to follow many of my patients. I simply was not able to let go of my routine. By ignoring the reality and the upcoming extended period of hiatus for the treatment of a serious illness, I was using work as a way to feed my denial.

Prior to my cancer surgery, I would stand next to my oncologists during my appointments, and we would look at my images and discuss my case as if we were talking about a mutual patient of ours. By pretending to be the doctor of someone else, I would appear to be the most compliant and calm patient. It was only in the postoperative period after the undeniable trauma of the surgery that I was able to transition from being a physician to being a patient. It finally occurred to me that I was not the attending physician anymore; I was the one who had cancer and was receiving treatment.

Patient Inconveniences

As a patient, I experienced the inconvenience of “medical routines” firsthand. While I understand the necessity of chest x-rays, blood tests, and urine cultures when I had a fever, especially in the context of postchemotherapy neutropenia, the process struck me as irritatingly intrusive, especially when it happened in the middle of the night. After all, that was when I felt weak with fever, chills, abdominal pain, diarrhea, dry mouth, and headache.

All the testing that goes along with cancer can be tiresome. Getting a CT scan with intravenous and oral contrast is not an easy feat. Each time I received intravenous contrast, I would have intense nausea and vomiting. Even the oral contrast required drinking about half a gallon of thick liquid that is completely unpalatable even though it tastes like strawberry, banana, apple, or grapes. Knowing that the taste is chemical made each gulp a small challenge.

Some of the testing can be isolating in both a literal and figurative sense. Lying in the bed of the PET or CT scanner, I felt as if the automatic instructions from the machine, and even the voice from the technician outside of the room, were alien and distant. The feeling of isolation can easily cause a person to regress to a more vulnerable state.

One island in the storm was patient-controlled analgesia. I was grateful for the chance to control the dose and timing of the medicine for my pain. I understand now that the potential of pain is a big part of a patient's suffering. When you give patients the chance to plan and implement their own pain control, the sense of relief is priceless.

Medicine And Statistics

Prior to my cancer, whenever I used statistics as a part of shared decision-making with patients, I expected them to understand that medicine is a science, albeit an imprecise one at times. However, many patients wanted absolute, yes-or-no–type answers. It is not uncommon for patients to regard statistics as irrelevant. In the past I considered such patient behavior a result of a lack of scientific background. Now, I feel the cold objectivity and the businesslike nature of statistics.

Surely, a physician should endeavor to be as objective as possible, while remaining tactful in the delivery of unfavorable information. This objective yet tactful stance can be viewed by patients as distant and detached. As a physician, when I heard patients or their family use terms such as “you doctors,” I would feel disparaged and unappreciated. Now I know that patients who feel helpless and afraid may see a world divided. When I was suffering, I felt alone, caught in the middle of the evil disease and people who were trying to get rid of it. I was a passive, powerless entity in the process. Such a mindset can cause one to become defensive and critical of others. When one feels voiceless in the decision process, it is hard to view the care team as on one's side.

Before the cancer, my body was a quiet supporter of my ambition. Ironically, it was in sickness that I felt the strength inside me. When I looked in the mirror and saw a thin, pale, bald-headed person looking back at me, I could feel the strong vitality inside my head. I alternated between feeling trapped inside my broken body and the resolve of seeing that caring for this frail physical being was an exercise to get my mind in shape. What a contrast in health and spirit: a worn-out shell versus a sharp consciousness!

There is a duality of thought when one considers the time one spends in the sick bed: the age-old quantity versus quality conundrum. On one hand, it is time one would not otherwise have if it were not for modern medicine. On the other hand, it is time lost because the quality of the time is diminished by treatment that renders one sick and weak, preventing the enjoyment of life. One sacrifices the quality of today in the hopes of having a better future.

Other Lessons

Cancer taught me several lessons as I transitioned from the role of a doctor to patient. One lesson was an appreciation for the “teaching burden” that patients have to shoulder. Residents came to my room and took my medical history, going over a lengthy review of systems, performing a thorough physical exam. We should all be thankful to patients for lending themselves to the training of our new physicians.

Another lesson came from the opening of oneself to total strangers. During my cancer treatment, as I met the flow of new physicians, such as an anesthesiologist before the surgery, I felt a distinct recoil in my gut. This thought remains with me when I meet a patient in the emergency room or hospital ward for the first time. I cannot help but wonder how they feel when I, a heretofore unknown entity, propose an invasive procedure such as cardiac catheterization. Do they feel the same uncertainty I felt as a patient? It certainly gives one pause.

Even basic, everyday medical equipment took on new meaning for me after cancer. During one of my chemotherapy infusions, I had sudden hypotension and bradycardia, to the point that I passed out. When I came to, I saw a crash cart next to me and was struck with fear. Now, whenever I see one, I am emotionally transported back to that moment and feel a vague but real threat emanating from it. Perhaps to patients—not just children, but also adults—who have experienced emergencies and life-threatening conditions, many pieces of equipment regularly used by doctors and nurses could evoke a similar emotional response of fear, dread, or anxiety.

My journey through cancer has given me a new appreciation for the nuanced perspective a patient requires. In the past I would sometimes hold my patients' hands and say, “I understand how you feel.” Now I say, “Although it is impossible for me to know exactly how you feel, I will try my best to understand you and see things from your side.”

These are the insights I have gained from being a patient. Doctors and patients are alike. Life experiences help us to see other people's points of view. The success of any treatment relies as much on the kindness and forgiveness we show to each other as it does on medical expertise and advancements. The latter is often limited by resources, whereas the former requires only a good heart.

Download alternative formats of this article, inlcuding PDF and e-reader versions at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4569245/ and download current or past issues of "Proceedings" here:http://www.baylorhealth.edu/Research/Proceedings/CurrentIssue/Pages/default.aspx.

作者岑瀑啸女士系美国佛罗里达医院心血管专科医生

照片由作者提供。美国大学、高中信息汇总系列:

美高留学被忽悠?数字说话(美高百校学费汇总)系列栏目部分链接

【美国大学、高中信息汇总系列】

【陈屹视线】 美国教育30年心经 (百篇原创)

............

【留美学子】 的 读者文摘

第 845 期 持续推出精彩 不链接任何广告

仰望星空、脚踏实地

长按【留美学子】二维码 订阅!

订阅!

最新评论

推荐文章

作者最新文章

你可能感兴趣的文章

Copyright Disclaimer: The copyright of contents (including texts, images, videos and audios) posted above belong to the User who shared or the third-party website which the User shared from. If you found your copyright have been infringed, please send a DMCA takedown notice to [email protected]. For more detail of the source, please click on the button "Read Original Post" below. For other communications, please send to [email protected].

版权声明:以上内容为用户推荐收藏至CareerEngine平台,其内容(含文字、图片、视频、音频等)及知识版权均属用户或用户转发自的第三方网站,如涉嫌侵权,请通知[email protected]进行信息删除。如需查看信息来源,请点击“查看原文”。如需洽谈其它事宜,请联系[email protected]。

版权声明:以上内容为用户推荐收藏至CareerEngine平台,其内容(含文字、图片、视频、音频等)及知识版权均属用户或用户转发自的第三方网站,如涉嫌侵权,请通知[email protected]进行信息删除。如需查看信息来源,请点击“查看原文”。如需洽谈其它事宜,请联系[email protected]。